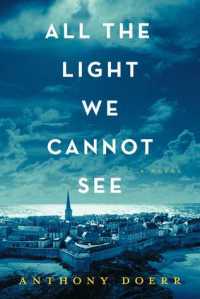

“All the Light We Cannot See” by Anthony Doerr is rated one of the top 10 best-selling books of 2014 by the New York Times, won the 2015 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, and was short listed for the National Book Award. With so many achievements following it, I had to pick up a copy and see what all the fuss was about. To say the least, I was not disappointed.

Told in present tense, almost lyrical prose, the story follows the lives of two children as they grow up during World War II and find themselves on either side of Hitler’s rise to power. Each chapter is short, sometimes less than a page, and jumps not only between the two children, but between different time periods. The story itself begins in 1944 when our heroine, Marie-Laure, is sixteen, and our hero, Werner, is eighteen. Then it jumps back to when they are children and bounces around between years right until the end. It can sometimes be hard to follow, but as a whole ends up working well to tell the story.

In 1934, six-year-old Marie-Laure loses her eyesight to cataracts. Her father, a locksmith at the Museum of Natural History, immediately steps forward to help her, determined to not let it ruin her life. He teaches her to read Braille and creates small replicas of their neighborhood and house for Marie-Laure to memorize so she can navigate her way around. He takes her into town on Tuesdays and has her lead them back home, which forces Marie-Laure to learn to count things like storm gates and trees and hydrants, until she can walk the streets without getting lost.

Her father brings her to work with him so she can learn from the other staff members. While there, she learns the tale of a mysterious diamond referred to as the “Sea of Flames,” which is said to curse whoever possesses it and was sent to the museum so no one would ever suffer the fate of it again. The diamond has a recurring role in the novel and creates an almost magical feel to the otherwise strictly historical genre this book is placed in.

At the same time, in a small town outside Germany, we learn about eight-year-old Werner, who lives in an orphanage with his younger sister Jutta after their father is killed in a mining accident. Werner, with his snow-white hair that often makes people stop and stare, is an ambitious, charming, curious child. One day he finds a broken radio and brings it back to the orphanage to fix. He is drawn to science and is naturally able to find what is wrong with the radio even though he’s had no prior experience with one. He seeks to fix more things, and it isn’t long before word of his talent extends to the locals. One day, a high-ranking official asks him to fix his radio and is so impressed with his work he tells Werner about a school where he can go to learn more about the things he is interested in. In their town, and perhaps most of Germany, when a boy turns fifteen he is sent to work in the mines. There is nothing that horrifies Werner more than working in the mine that killed his father, so he leans in the direction of the school.

Of course, the school is actually the horrific breeding grounds of boys who are being trained to be soldiers in Hitler’s army. By the time Werner learns this, it’s too late to get out. It appears the only way boys leave this school is by dying, so Werner tries to obey the rules and power through without losing who he is. When he graduates, his skills earn him a place in the Wehrmacht, where he tracks down the senders of illegal radio transmitters. But the job haunts Werner when, at the end of one of the radio signals, he finds a girl who has been shot in the head. There are still elements of the younger, ambitious Werner trying to break through in the older version of himself, and it’s heart-breaking to see him reflect on a time when science was something that created joy for him, not death and misery.

At the same time of Hitler’s rise, the museums of Paris work to hide all their treasures. Marie-Laure’s father is trusted with the Sea of Flames, or one of the replicas of it – no one can be sure if it’s the real one or not, for safety’s sake. When the Nazi’s invade, he and Marie-Laure flee to Saint-Malo to stay with Uncle Etienne, a very anxious ex-soldier who rarely ever leaves his house for fear of the outside world. One day, Marie-Laure’s father is arrested by Germans and doesn’t come back. Years later, when the Nazi’s are dispatched to the shores of Normandy, Etienne is also arrested and Marie-Laure is left alone. As part of who she is and her stubborn attitude, she finds herself joining the Resistance. At the same time, only blocks away from where she is, Werner is trapped under the remains of a hotel.

Doerr creates a parallel between Marie-Laure and Werner before we ever see them meet. Marie-Laure is somewhat of a prodigy; she devours large books quickly and is able to crack any puzzle her father presents her with within a few minutes. Werner is also a prodigy; he can easily fix things that even professionals struggle with and he passes his entrance exams with flying colors. Beyond that, there is also the parallel that concerns the title of the story. In Marie-Laure’s case, the light she cannot see is the obvious one we tend to think of – the light of the world, of existence, that only eyes can pick up. For Werner, the light refers to a discussion he hears when he is younger on a late-night radio broadcast about the brain’s ability to create light in the darkness.

The characters finally meet toward the end of the book. Their first encounter, told from Werner’s point-of-view, is awkward. When Marie-Laure emerges from the house instead of Etienne, Werner seems strangely fascinated with her and follows her down the street. Later, after Werner picks up her voice on one of the radio signals and tracks her down to save her, they have another awkward encounter. This time Werner actually talks to her, instead of stalking her, and helps her out of her hiding place. This is the only point in the novel where things seem to fall flat. There is never any place where you doubt the age of Werner – he sounds young, is often referred to as being small, and carries an air of youth around him. With that in mind, his meeting with Marie-Laure makes it seem as if he is eight years old again. The entire scene moves too easily, as if the two have been friends since they were children. Marie-Laure is not afraid of him (what happened to not trusting strangers, Marie?) and they talk casually to each other about things from their past and how hungry they are. Marie-Laure shows him around and they eat peaches and hide out until it’s safe and fall asleep talking to each other. It makes them both appear a lot younger than they really are, and much younger than they’ve both acted throughout the previous scenes.

When they wake again, Werner leads her out of the house and takes her to safety. Before they depart, his inner monologue says, “Her voice like a bright, clear window of sky. Her face a field of freckles. He thinks: I don’t want to let you go.” It’s the kind of interaction one might expect to find in a love story – the sudden attraction to an almost complete stranger, the familiarity shared between them in their first words. In other contexts, it would work well, but falls short here because of all we know about these two characters before they meet up.

Still, it’s disappointing to see them part so quickly when it takes so long for them to get together. Doerr has a way of using beautiful descriptions and crisp sentences to make us truly and deeply care about these two kids. He paints France and Germany into a perfect picture, capturing the essence of war while maintaining the transition of growing up. Doerr’s novel does not disappoint and will appeal to a wide variety of audiences. In the end, I can honestly say I’m glad I decided to read this book and will recommend it to anyone willing to listen.